Well, my goal tonight was twofold: first, to explain the changes we made in our Army in 2006; and, second, to give a speech that I’d like to think Irving Kristol might have enjoyed.

—Gen. David Petraeus, May 6, 2010, speech to the American Enterprise Institute

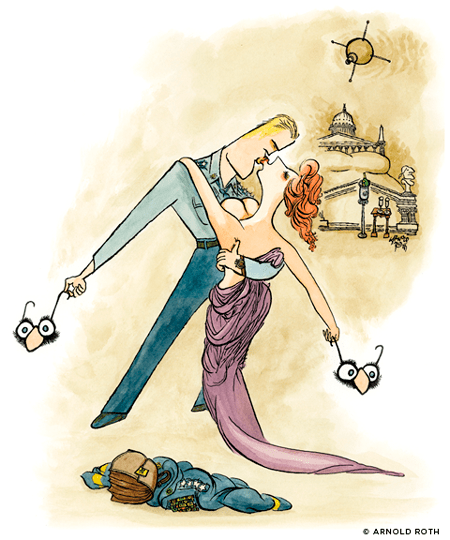

It was an aberration, a break from the exemplary pattern, and so David Petraeus’s fall from power was a tragedy. At least that was the story in all the usual places. Once Petraeus loosened his legendary personal discipline long enough to let a biographer roll around under his desk, all the conventional armature of meritocratic achievement fell away as if by magic.

As Tara McKelvey explained on The Atlantic’s website around the time the great general’s dalliance became public, Petraeus was like “a hero in a Shakespearean tragedy”: “Military men, and especially retired officers who head up the CIA, are supposed to be icy and methodical, even more so now that killing is done remotely through aerial drones. Journalists are supposed to cover these issues in a dispassionate way. Neither side is being honest, and the fact that he fell for her, and she for him, is a reminder of our common humanity.”

In a less epic but still impressively pretentious register, The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik counseled tolerance with all the chastened sagacity of a middle-aged oracle. “Desire,” he observed, “is not subject to the language of judicious choice, or it would not be desire, with a language all its own.”

It was all just a terrible mistake, and we shouldn’t judge. This is what happens when the American meritocracy finally repairs behind closed doors to go fuck itself.

Thrice Cursed

In the narrative of the pundit class, Paula Broadwell was plowed by Cincinnatus.

Or, to invoke the abstract formulations favored by the Gopnik set: a four-star narrative construct was caught last year rubbing its actual body on a particularly vigorous narrative constructor. The harsh light of public exposure thus brutally cut short the public service of a humble soul who had risen from obscurity to heal a clinically depressed military occupation. As the longtime journalist Thomas Ricks constructed his own pleasing version of the David Petraeus character, the general’s selection to command the war in Iraq “expressly was not the choice of the military. He was regarded by many of his peers as something of a thrice-cursed outlier—an officer with a doctorate from Princeton who also seemed to enjoy talking to reporters and even to politicians and who had made his peers look bad with his success leading the 101st Airborne Division in Mosul in 2003–4.”

Here, dear reader, you must summon patient compassion. Try to imagine the hardships of a military officer triply burdened by close relationships with political leaders and the national news media, an Ivy League PhD, and wartime triumphs leading an elite airborne division. Our hero somehow survived in spite of it all. He rose against his handicaps, triumphing over the awful mark of Princeton University, that great gathering place for outcasts, rebels, and the socially obscure. He secured higher military rank even though he had been successful in combat. He adroitly worked CBS News, the Washington Post, and the United States Senate, yet still rose to prominence.

Another humble fact about Petraeus that Ricks forgets to mention: as a freshly minted West Point graduate, barely commissioned as a second lieutenant, the future Princeton PhD brought still greater adversity down on his head by marrying the daughter of West Point’s commandant, an army general who would hang around and impede his son-in-law’s career path with the taint of high rank and considerable institutional power. It’s really a miracle this Petraeus person ever amounted to anything, isn’t it?

Der Putz

The American political press is willfully blind to power, the pursuit of power, and the operation of power. And practitioners of the craft usually elect to make up for their habitual neglect of the blindingly obvious by compulsively personalizing the political. In this strategic alignment of blind spots, transactions and schemes become happy accidents: a West Point cadet marries the daughter of the West Point commandant, earns a doctorate, and yet somehow succeeds in the military.

Or take Paula Broadwell, who at Century High School in Bismarck, North Dakota, managed to be the student body president, the homecoming queen, a basketball star, and the valedictorian. “By the end of her senior year,” a creepy newspaper story later explained, “she’d held nine leadership positions at Century and had been involved in 24 extracurricular community activities.”[*] Then she went to West Point, then went on to earn two master’s degrees, then worked as a research associate at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, then left to pursue a PhD in a highly regarded military studies program in London—and at last she let her passions run away with her, accidentally bringing her to greater connection and intimacy with an increasingly prominent government official. She was, as you can see, a girlish daydreamer, an unfocused wanderer swooning in her momentary passion. Her feet were swept out from underneath her. She was tickled and she giggled; cue fate.

This is what happens when the American meritocracy finally repairs behind closed doors to go fuck itself.

Luckily, the former student body president and homecoming queen and valedictorian and Harvard associate somehow managed to avoid being helplessly attracted to, say, a handsome and virile staff sergeant. No, Broadwell fell for Petraeus. The products of her desire were a book deal and a spot on The Daily Show, but the desire itself was not subject to the language of judicious choice. There was no icy judgment, like when human beings are killed by drones. Doesn’t every passionate combat zone love affair lead to a contract from a publisher?

Back at The Atlantic, Tara McKelvey recounted her personal interactions with Broadwell, the swooning girl who had been swept away by bad judgment and her swollen ladyparts. At a party in Washington, D.C., attended by journalists and government officials, McKelvey mentioned that she had been unable to get Petraeus to sit down with her for an interview. “I’ll talk to him about it,” Broadwell replied, announcing her personal access to the director of the Central Intelligence Agency in a room full of people who live and die by access to senior government officials. She was supposed to be icy and methodical, but she fell for him.

And still McKelvey managed to miss the point. She would later come to discover Broadwell’s sexual affair with Petraeus, an act of coupling that she would find disturbing. “Equally troubling,” McKelvey concluded, was the revelation that Broadwell “was cashing in on her relationship, gaining a national profile and speaking gigs because of her book.” The person who announced at a D.C. party that she could call the CIA director and get him to do things for her turned out to be—wait for it—cashing in on her relationship. Tara McKelvey will one day discover that liquor stores don’t sell their product just to be festive, and her local Mercedes dealership isn’t merely part of a well-appointed floating global party run by car enthusiasts.

But McKelvey was surely not alone in her failure of perception. Here’s Adam Gopnik again: “The point of lust, not to put too fine a point on it, is that it lures us to do dumb stuff, and the fact that the dumb stuff gets done is continuing proof of its power. As Roth’s Alexander Portnoy tells us, ‘Ven der putz shteht, ligt der sechel in drerd’—a Yiddish saying that means, more or less, that when desire comes in the door judgment jumps out the window and cracks its skull on the pavement.”

Sitting in the heart of the empire, surrounded by schemers and climbers, journalists watch a pair of particularly methodical careerists work one another for the enhancement of their power and status, one getting to write a book for a national press and one getting to be the subject of a fawning book celebrated in the national press. The passion, the journalists say. The putz apparently shteht, and so pfft. He fell for her, and she for him, and it’s a reminder of our common humanity.

Do you trust people who reach this conclusion from the available set of facts to understand or explain anything at all to you?

Massaging Kimberly’s Institute

If you are determined to track the real governing passions of our military elite, however, you must be prepared to brave a world far more unsightly and seamy than anything summoned by the urgent coupling of the forever climbing amour-propre of Lady Broadwell and Commander Petraeus.

Rajiv Chandrasekaran, one of the last journalists in the imperial city who apparently notices anything at all, wrote one of the shrewdest political stories of 2012. It produced an immediate firestorm of not being noticed very much. The topic of the story was David Petraeus and his personal relationships in war zones, and it doesn’t matter that there was no sex in it.

Even in Chandrasekaran’s quite cunning narrative, some conventional newspaper framing creeps in. Start with the first sentence: “Frederick and Kimberly Kagan, a husband-and-wife team of hawkish military analysts, put their jobs at influential Washington think tanks on hold for almost a year to work for Gen. David H. Petraeus when he was the top U.S. commander in Afghanistan.” No they didn’t, and the story that this sentence introduces makes it clear that they didn’t.

If you are determined to track the real governing passions of our military elite, you must be prepared to brave a world far more seamy than anything summoned by the amour-propre of Lady Broadwell and Commander Petraeus.

The Kagans are a curious pair, only tangentially trained and experienced in their area of putative expertise. They’re like surgeons who did their postgraduate training entirely in cellular biology: their experience is not irrelevant to the tasks at hand, but it’s also not the task at hand—and you kind of wish they had been taught to use a scalpel before they started cutting into your chest. Kimberly holds a PhD in ancient history; Frederick, identified by Chandrasekaran as an expert in “the Soviets,” wrote a dissertation titled “Reform for Survival: Russian Military Policy and Conservative Reform, 1825–1836.” Neither had contemporary strategic training or experience; neither has ever spent time in the military.[**] But the name counts: Donald Kagan, Frederick’s father, and Robert Kagan, his brother, are prominent neoconservatives who played a substantial role in the now-quaint Project for the New American Century, which, among other things, helped to choreograph the immensely wrong-headed 2003 invasion of Iraq. And the Kagans had already used their so-called expertise to argue that Petraeus should be given more resources and more power; indeed, in 2006, Frederick Kagan’s research for the American Enterprise Institute “provided the strategic underpinning for the troop surge Bush approved in January 2007.” So the Kagans’ expertise was just right.

With those credentials, Kim and Fred hung out at Dave’s headquarters like old roommates, nestling down in Afghanistan for months at a time. As Chandrasekaran writes, Petraeus made the pair “de facto senior advisers, a status that afforded them numerous private meetings in his office, priority travel across the war zone and the ability to read highly secretive transcripts of intercepted Taliban communications.”

Petraeus also flattered and seduced the Kagans like a particularly shameless lover, telling an audience—in their presence—that the pair “grade my work on a daily basis.” Thus tickled, they cooed in the language of institutional love. “In March 2009, they co-wrote an op-ed in the New York Times that called for sending more forces to Afghanistan,” a conclusion curiously like the one Frederick had reached three years earlier about the Iraq mission. And the party kept going until everybody had gotten off three or four times and the front desk clerk was pounding on the door and shouting something about checkout time:

The Kagans said they continued to receive salaries from their think tanks while in Afghanistan. Kim Kagan’s institute is funded in part by large defense contractors. During Petraeus’s tenure in Kabul, she sent out a letter soliciting contributions so the organization could continue its military work, according to two people who saw the letter.

On August 8, 2011, a month after he relinquished command in Afghanistan to take over at the CIA, Petraeus spoke at the institute’s first “President’s Circle” dinner, where he accepted an award from Kim Kagan. To join the President’s Circle, individuals must contribute at least $10,000 a year. The private event, held at the Newseum in Washington, also drew executives from defense contractors who fund the institute.

Petraeus got a connection to a family of prominent neoconservatives who held posts at hawkish think tanks, influenced Republican politicians, and had easy access to the leading op-ed pages; the Kagans got to draw their salaries while writing fundraising letters from his headquarters; and then they gave him an award at a dinner funded by the companies that sold the products he used to make war.[***] The Kagans, in other words, put their jobs at influential Washington think tanks on hold to volunteer at a general’s wartime headquarters. Then Paula Broadwell wandered in, and passion took over.

Husky Groaning

Transactional sex is about as alien to the U.S. military as heat is to fire and water is to fish. Away from home for a year and more at a time, soldiers borrow, buy, and approximate sex with anything that floats by. This is not a secret. It recurs as a reformist theme throughout the history of modern warfare; much as the Committee on Protective Work for Girls took on volunteers to patrol army posts during World War I and sternly rebuke anything too plainly feminine lurking near military personnel, the American military irritated servicemembers during the Iraq War by making payment for sex a violation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[****] The contemporary Middle East is the military’s Las Vegas: what happens on deployment stays on deployment. It could not have been a secret that General Petraeus had a special visitor at his headquarters in Afghanistan, and it would not have been regarded as unusual or shocking.

But sex in military settings also reflects power. It has a rank structure and institutional implications. In fictional armies, as in real ones, men marry into power; officers, like princes, form alliances through strategic coupling. And the ability to couple is a basis of power.[*****]

The person who announced at a D.C. party that she could call the CIA director and get him to do things for her turned out to be—wait for it—cashing in on her relationship.

Once an Eagle, a 1968 novel by Anton Myrer, a Marine Corps veteran of World War II, charts the course of two infantry officers in the twentieth-century U.S. Army. Army officers regard it as a how-to manual and a description of a long cultural war inside their own institution. The book describes a sustained competition for power between Sam Damon, the working-class protagonist, and Courtney Massengale, his antagonist from a privileged background. (In a triumph of military efficiency, everything you really need to know about these characters is telegraphed in their names.) Damon is kind to enlisted men, skilled in combat, bored by internal politics, and married to the hot daughter of his battlefield commander. Massengale is a preening staff officer, resolutely political and reflexively contemptuous of subordinates.

He is also, of course, unable to have healthy sex with women. “He was weeping now, a dry, husky groaning,” goes a sex scene with his young wife. “Was this what men did?”[******] Massengale’s manly inability with his wife is very precisely a reflection of his inability to lead men under fire despite bossing them around on post: “She had assumed he would lead in this, as he had in everything else,” his wife thinks, splayed out beneath him but barely led at all. She gets her hands on a medical journal, later, and looks up “ejaculatio praecox.” Weeping, groaning, collapsing in a helpless pile moments after he has begun: not really a soldier.

Thirty pages later, Damon is deployed overseas, sent to prepare for war. Massengale lingers in safety back home, and he ends up alone with Damon’s wife, who is brought to arousal by his strutting posture of command. They should be a couple, she realizes, suddenly knowing that she married the wrong man. “Oh, we two, together—do you realize what we could have accomplished?” Massengale asks her; his sexual power promises accomplishment, the commencement and completion of ambitious tasks. And so she finds herself “adrift on a sea of yielding,” desperate to be incorporated into his command presence as she ponders the potential of its power over other men. Other men, and therefore women: “‘Take me,’ she breathed. ‘Please. Take me now.’” And then he can’t. “His eyes were full of fear now; she could see it clear as day. . . . It was all clear to her now, what no one—not Fahrquahrson or MacArthur or the AG’s office or the Chief of Staff—knew about Courtney Massengale. She knew; but the cost, the cost of knowing—!”

All of this has happened in the rain, and Massengale has covered Damon’s wife in a military jacket, his own costume from a party. She begs to be fucked while covered in the uniform of a soldier, then removes the coat and returns it, bitterly, when he fails to do the fucking. “She yanked the hussar’s jacket off her head and shoulders and flung it in his face. ‘You dirty—oh God, oh God, you coward!’” Cowardice in battle, failing to lead a uniformed subordinate: still not really a soldier.

This narrative blending of sexual power with martial prowess is familiar enough that someone was bound to suggest it in the wake of the Petraeus affair, and one of the usual someones did. “History offers some rough guidelines to the real men who wore masks of command,” wrote National Review military pundit Victor Davis Hanson—like Kimberly Kagan, an armchair strategist principally schooled in ancient history and the classics—a few days before Christmas. “In a word, many of the best were as pursuant of women as they were of the enemy—and the former did not seem to impair the latter.”

David Petraeus worked in an environment in which everyone was getting something for their involvement. Volunteering, the Kagans drew salaries; getting nothing for their effort, they wrote fundraising letters for their think tanks, then used some of the cash to reward the person who gave them a desk in a war zone to write those letters. (And for good measure, the site of the awards ceremony was the Newseum, the Gannett-funded monument to the achievements of the capital’s obedient stenography-elite—a stirring vision, all in all, of access as its own reward.) The cultural knowledge surrounding all these transactions was that the best warriors pursued women like they pursued the enemy. And yet a general somehow came to have a sexual affair with his much younger hagiographer, getting something and giving something and ending up with yet another person willing to gush about his brilliance to a credulous nation.

Desire, I mean to say, is not subject to the language of judicious choice.

[*] The story, in the Charlotte Observer, reports at remarkable length on the post-divorce bickering that went on between Broadwell’s parents. Readers learn, for example, that in November 1982 her father demanded that his ex-wife return “a family heirloom sausage maker, his accordion from childhood and his golf gear.”

[**] If you have never seen Frederick Kagan speak, do yourself a favor and find some online video. You will be fairly certain, after a few minutes, that Lumbergh took Frederick Kagan’s stapler.

[***] In a letter to the editor, fellow think tanker Anthony H. Cordesman wrote that Chandrasekaran was being terribly unfair about the whole thing. Indeed, Cordesman knew the Kagans while they were bunked down with Petraeus, and “never saw them act as ideologues or misuse their access.” And he was correct: writing fundraising letters from Petraeus’s headquarters and soliciting contributions from defense contractors so they could come to a dinner where the Kagans celebrated their patron, they were not misusing their access; they were using it for precisely its intended purpose.

[****] Next, they’re going to tell us we can’t drink or only on the weekends,” Sgt. 1st Class Henry Mims told Stars and Stripes.

[*****] Though some Air Force generals are known to withhold the life essence.

[******] Are you in pain?” his wife asks him—twice.